The temple is located in Wayao village, in the Sichuan region, and it consists of two stories, both of them painted. The restoration project was part of the training program sponsored by the Kham Aid Foundation, supported by Winrock International, Millepede Foundation and private donors and carried out in collaboration with John Sanday Associates. A local team composed by 11 trainees carried out the preservation of the wall paintings. The local team received guidance from Luigi Fieni and 5 members of the Wall Painting Conservation Team of Mustang, Nepal.

kyi lhakhang

state of preservation

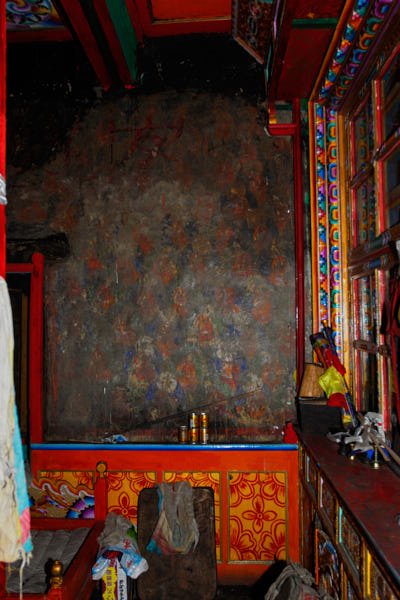

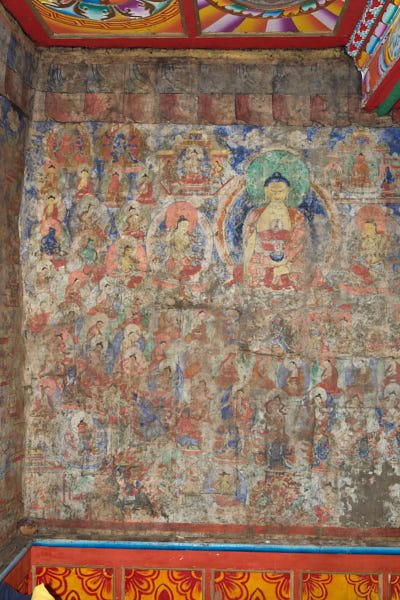

The quality of the wall paintings varies remarkably from the first to the second floor. The paint layer on the first floor is much rougher than the second floor and the style of painting appears to be much more recent than the upper floor. Inconsistencies in the pictorial cycle of the images on the first floor suggest that it was probably repainted. The structural wall of this temple was made of stones piled up apparently without binder. On top of the stones, a coating of clay mixed with straw was applied to create a kind of even surface to host the pictorial layer. The thickness of this coating varied greatly, according to the voids created by the irregular stones constituting the wall. The binder of the paint layer in all the stories was water based as taht is the tradition with most of the Tibetan art.

First story: the painted surface covered the four walls. Nearly half of the preparatory layer was heavily detached from the stone based wall and many areas would not sound still, thus being in risk of falling off. The paint layer presented over paintings on the main deities: due to damages, local artists had painted over them to allow the local community to worship their deities. Dust deposits and cobwebs were spread all over the surface of the paint layer. The architraves were painted as well in such a rough way that many drops of enamel had been spilled over the paint layer.

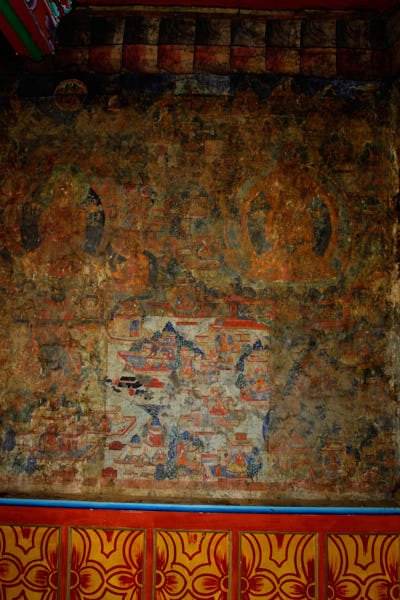

Second story: the painted surface covered three walls only for there was a huge altar all along the forth one. The state of preservation was extremely appalling for the wall paintings had been subjected to vandalism acts and they were severely damaged. More than 30% of the paint layer was randomly detached from the stone based wall and several cracks were present on the painted surface. The protective varnish turned brownish with ageing and it would impede a clear vision of the pictorial cycle. On top of that, the wall paintings had been over painted with writings in Chinese and Tibetan with a deep red color.

Furthermore, the paint layer was covered with a thick coating of mud, in some cases more than 3 mm. Oral memory from the local community recounts that this story had been used as a kitchen for a long time so that almost everything in the room was covered by black soot and grime. Luckily, the coating of mud had protected the murals. Local people had tried to clean that coating and the black soot as best as they could. As a consequence, they managed to damage seriously the lower section of the paint layer on all the three walls. On the south and west side, some patches of painted canvas were pasted onto the wall paintings.

Wooden ceiling: the ceiling in the second story is made of a series of interlocked wooden painted panels. The majority of the panels were over painted in 2004 and only 3 panels depicting mandalas had been left untouched. After some cleaning samples were carried out, it came out that all the panels still presented original paintings underneath. Although all of them were heavily darkened from the application of a very old and altered varnish, the paint layer was still looking in good conditions. Between the varnish and the over paintings laid a thick deposit of soot from smoke.

intervention of restoration

First story: the preparatory layer was fixed back to the stone based wall through injections of mortars and gluing solutions based on PVA binders. The small detachments were filled up with an acrylic emulsion dispersed in water. As for the deepest detachments, they were filled up with a mortar composed of local clays and a PVA binder. Tests were carried out to find out the most suitable clays to be injected. The mortar was then made of 2 kinds of local clay mixed with a PVA binder. Prior any injection, a surfactant solution was instilled through syringes. Where it was possible, existing cracks were used for the injections but in most of the cases, holes had to be done using hand-drills with bits whose width varied from 1 to 2 mm of diameter. Care was taken while drilling in order not to damage important outlines, figures or inscriptions. Since the amount of water in any mortar or solution would evaporate, some detachments could still not sound still underneath the surface of the wall paintings. Thence, the consolidation was checked every few weeks for the whole length of the project and more injections were carried out where needed.

Second story: the consolidation of the wall paintings was more complicated in this case for the paint layer was covered by a thick layer of mud and it was not possible to drill without risking to pierce important images or inscriptions. Thence it was decided to carry out the removal of the mud from the wall painting first, to allow the restorers to see where they were going to drill the holes needed for the injections. The consolidation process followed the same procedure performed in the first story.

So the cleaning was divided in two stages. The first one, the removal of the mud coating, was carried out using surgical knives and sharpened spatulas. Since the coating was too hard to be worked on, compresses of cotton soaked in a surfactant solution were applied on the surface to be cleaned for a period of 4 hours. After the removal of the compress, an hour was needed before any action be taken because the softened paint layer could have been removed together with the mud. In this way the paint layer could dry sufficiently and the removal of the mud was possible without any harm for the painting.

The second stage consisted in removing the darkened varnish with chemicals. The cleaning was carried out through Japanese tissue paper by absorption of the swollen varnish into the tissue and the cotton swab. A solution of two different formulas of EDTA in water were used for that purpose: wet Japanese tissue paper was applied to the paint layer to avoid that accidental abrasion of the cotton swabs, soaked in the solution, could harm the paintings. The use of EDTA solutions was followed by the use of a weak solution of Arabic gum to refine the cleaning.

The tissue paper was removed only after the cleaning was finished and a new tissue paper was applied in order to remove any possible deposit of the salt through the use of distilled water. The upper section of the wall paintings didn’t have the coating of mud probably because it was already blackened when the application of the mud took place. This cleaning was performed with the use of organic chemicals, applied directly on the thick deposits of soot and grime.

Wooden ceiling: Three mandalas were present on the ceiling of the second story: they looked contemporaneous to the murals. They were painted on square panels made out of different wooden planks. After the mandalas were removed from the ceiling it was noticed that some of the planks did not adhere properly and they might have separated. It was decided to glue the planks after the cleaning because the chemical used for that purpose could have melt the binder used for fixing the planks. All mandalas were cleaned off the varnish and the soot deposits employing cotton swabs soaked in organic chemicals. Soon after, the planks were glued with a PVA binder and they were protected with a 3% solution of Paraloid B72.

Plastering: cracks, fissures and holes were plastered up to the level of paint layer with a local clay mixed with a PVA binder. The surface had to be previously wet with 10% PVA solution in water in order to enhance the adhesive power of the plaster.

Retouching: a sample of retouching was carried out on a small section on the eastern side of south wall. Watercolors were used to match abraded or missing colours with the original paint layer.

the end

Unfortunately the project was stopped in 2008 following a ban imposed by the Chinese Government in all Tibetan areas soon after the infamous riots broken out in Lhasa and Chengdu in occasion of the Olympic Games. All of a sudden foreigners were not allowed anymore to work in sensitive areas, thus influencing the destiny of this project. Later on the foundation supporting the project closed down and the project could never be finished.