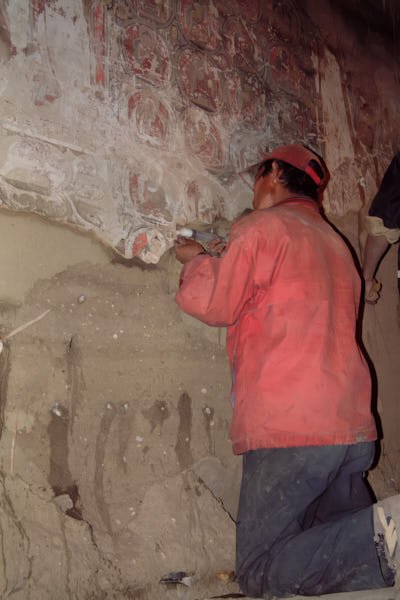

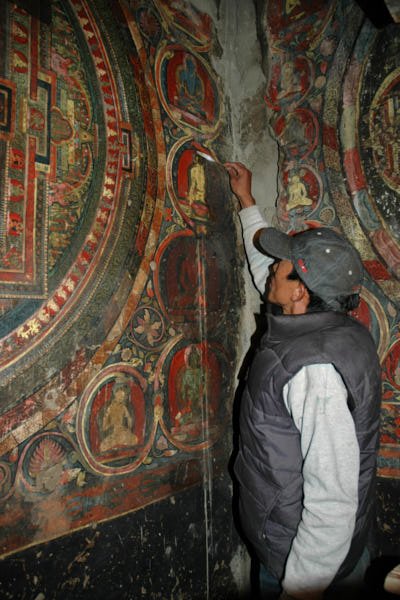

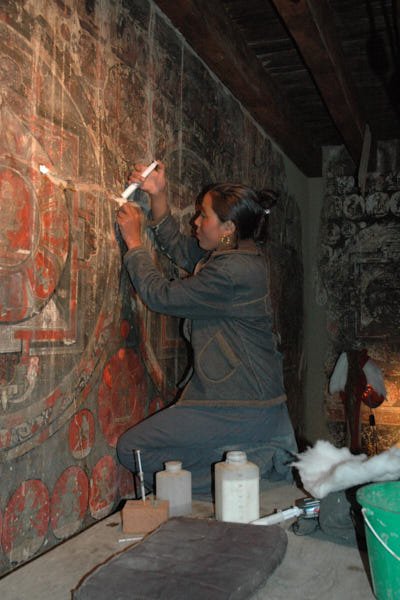

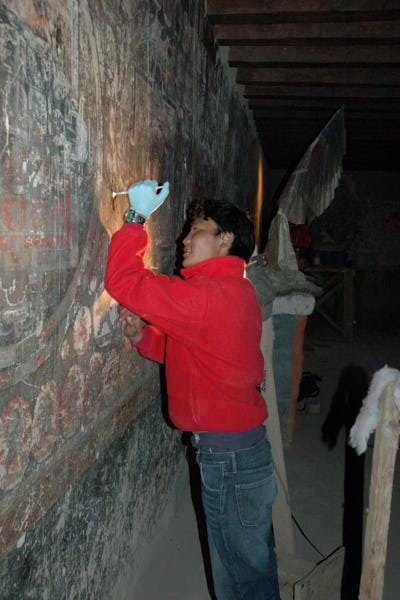

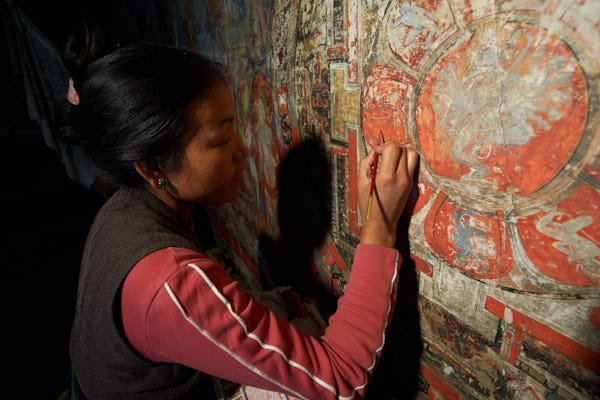

The restoration of this temple, started in 2001 and sponsored by the American Himalayan Foundation, was carried out by John Sanday Associates until 2008: from 2009 onwards the project was handed over a local foundation. Besides the conservation and restoration of mural paintings the main component of the project was to train and form a group of locals from Mustang, mostly farmers, to learn the skills of conservation and restoration.

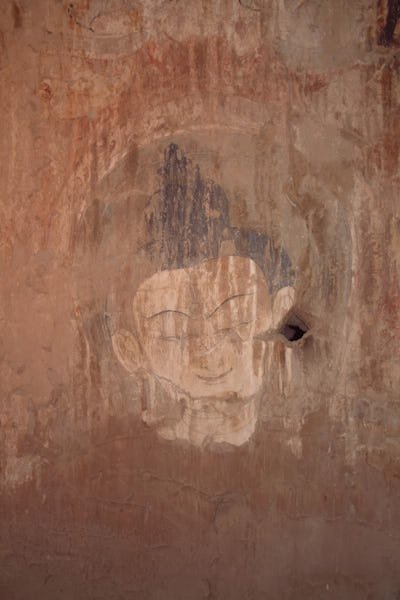

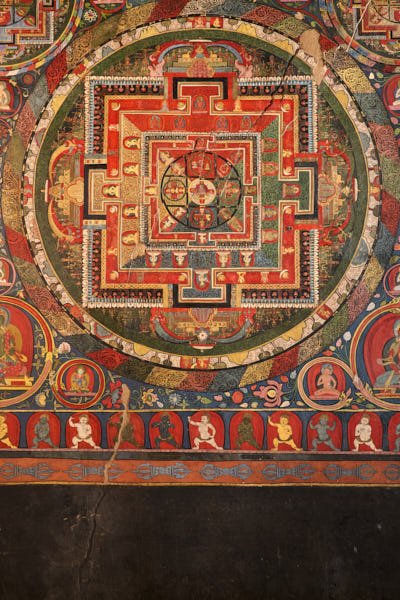

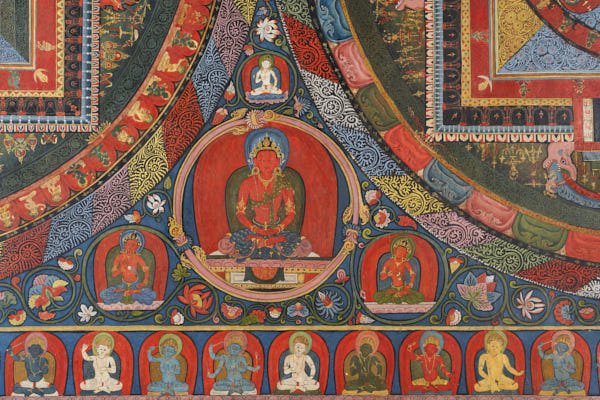

The temple was consecrated most probably in 1448 and it is divided into three stories, each painted with an extraordinarily detailed secco technique on clay. The first story contains a series of deities, while the other two floors present an extraordinary sequence of mandala. An impressive throne links the first to the second floor through the statue of Maitreya Buddha, re-erected in the 17th century.

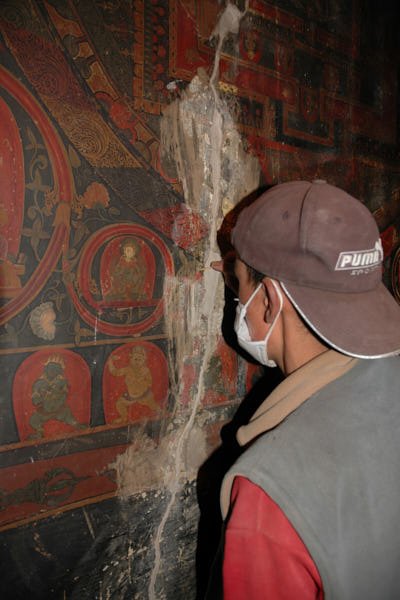

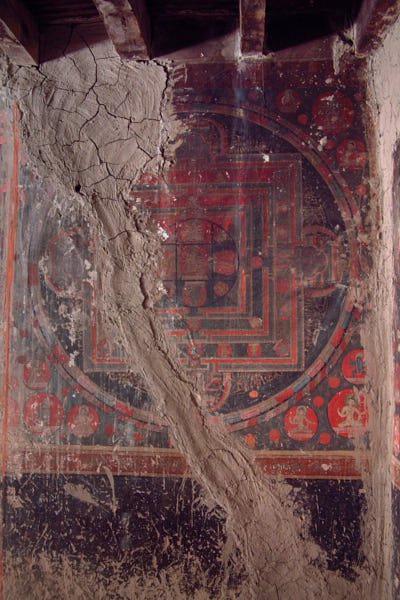

Each of the three floors had serious structural problems, for all the corners had become separated by several centimeters, most probably as a result of an earthquake. Moreover, the preparatory layers were detached by a few centimeters from the wall itself. In addition, water infiltrations from the ceiling had washed away a good portion of the paintings on the north wall of the second and third floors. The first story was the most seriously damaged: the majority of the paint layer was not visible, as it had become completely covered in a thick coating of clay leakage.

International consultants were in charge for the setting-up of a program to repair, conserve and consolidate the wall paintings in Jampa Lhakhang as well as the setting-up and maintaining of a training program for to teach conservation of wall paintings on site:

2001/2004 - Rodolfo Lujan Lunsford - Lead conservator

2001/2011 - Luigi Fieni - Assistant conservator, Lead conservator from 2004

2001/2004 - Chiara Tedde - Assistant conservator

2005/2008 - Federica Bagaglini - Assistant conservator

2006/2008 - Davide Sciandra - Assistant conservator

2009/2010 - Nelly Rieuf - Assistant conservator

2009/2011 - Samanta Ezeiza - Assistant conservator